Published: February 2026 | By Dr Ezi, Founder of Hearty Talk

Understanding grief is a powerful first step to recovery. This pillar page serves as a comprehensive reference for anyone feeling lost in grief. Grief is not something to “fix” quickly—it’s a natural response to profound loss. Every heart’s experience is valid, with no timelines or rules.

What Is Grief?

Grief is the natural, multifaceted response to significant loss. Although most commonly associated with the death of a loved one, grief can arise after any major disruption to life, identity, or relationships. Psychological research shows that grief affects emotions, thoughts, behaviours, and even the body (Stroebe, Schut, & Boerner, 2017).

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines grief as:

“The anguish experienced after significant loss… often including physiological distress, separation anxiety, confusion, yearning, obsessive dwelling on the past, and apprehension about the future.”

(APA, 2023)

Grief is not a single emotion. It is a constellation of reactions that may include:

Emotional Responses

- Sadness, longing, or yearning

- Anger, guilt, or irritability

- Shock, numbness, or disbelief

Physical Responses

- Fatigue or low energy

- Sleep disturbances

- Appetite changes

- Tightness in the chest or throat

Cognitive Responses

- Difficulty concentrating

- Intrusive thoughts

- Confusion or forgetfulness

Behavioural Responses

- Withdrawal from others

- Restlessness

- Avoidance of reminders

Grief is distinct from:

- Bereavement — the objective state of having lost someone

- Mourning — the cultural or social expression of grief (Rosenblatt, 2017)

Grief is also different from depression, although they can overlap. Depression is a clinical disorder; grief is a natural process that typically softens over time (Bonanno, 2009).

Modern grief theory emphasises that grief does not disappear — it transforms. Many people develop a “continuing bond” with the person they lost, finding new meaning and connection as life moves forward (Neimeyer, 2019).

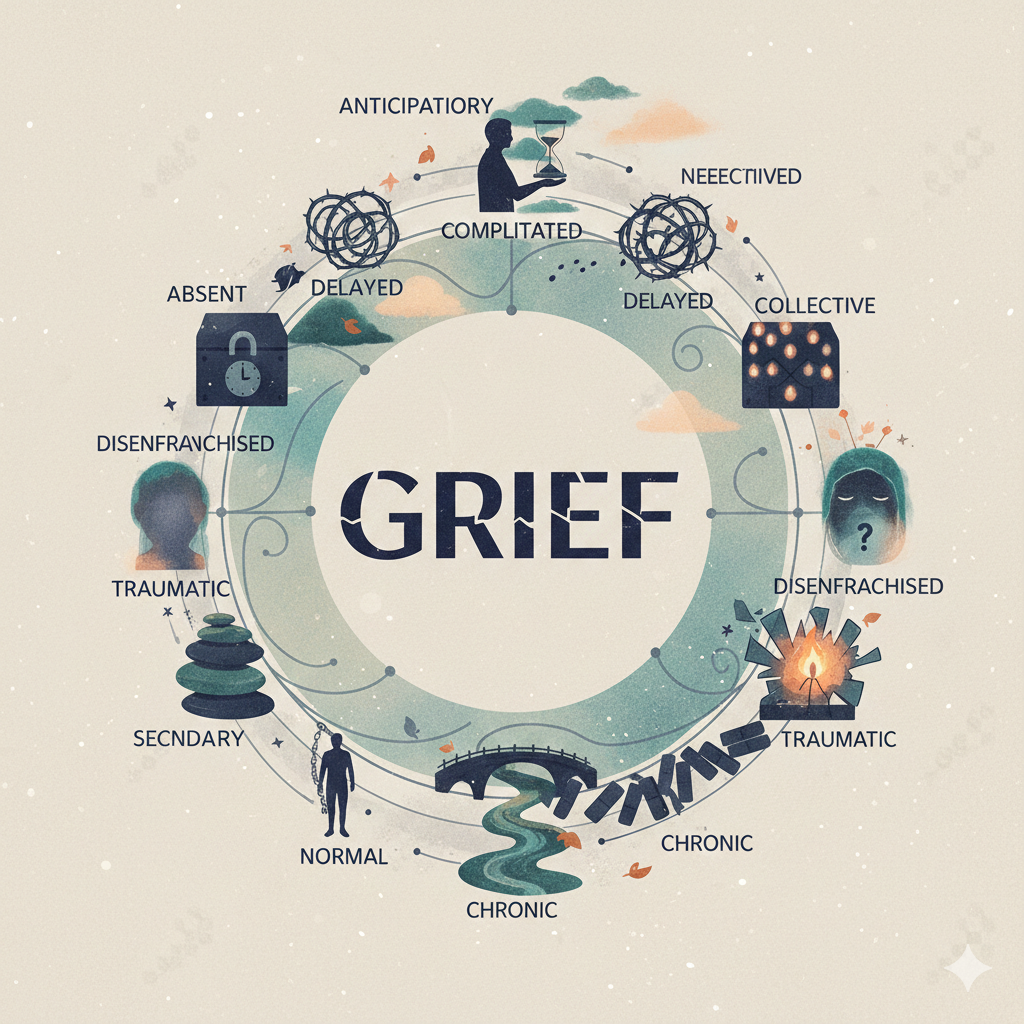

Types of Grief

Grief is not one-size-fits-all. Researchers identify several forms of grief, each with its own characteristics.

1. Normal (Uncomplicated) Grief

This is the most common and adaptive form of grief. Emotions may come in waves, gradually easing as the individual adjusts to life after the loss. There is no “right” timeline — grief is non-linear and deeply personal (Bonanno, 2009).

2. Anticipatory Grief

This occurs before an expected loss, such as during terminal illness or impending separation. It may involve sadness, anxiety, preparation, or guilt. Anticipatory grief can help people emotionally prepare, but it can also be draining (Shore et al., 2016).

3. Complicated Grief / Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD)

Some individuals experience persistent, intense grief that interferes with daily functioning. The DSM‑5‑TR defines Prolonged Grief Disorder as:

- Grief lasting at least 12 months in adults (6 months in children)

- Symptoms occurring nearly every day for at least the past month

- At least three symptoms, such as identity disruption, disbelief, avoidance, emotional pain, or intense loneliness

(American Psychiatric Association, 2022)

Risk factors include sudden or traumatic death, insecure attachment, prior trauma, or limited social support (Shear, 2015).

4. Disenfranchised Grief

Coined by Kenneth Doka (2002), this refers to grief that society does not acknowledge or validate. Examples include:

- Miscarriage

- Suicide loss

- Pet loss

- Loss related to addiction

Because these losses are often minimised, individuals may feel isolated or unsupported.

5. Ambiguous Loss / Ambiguous Grief

Described by Pauline Boss (2006), ambiguous loss occurs when there is no clear closure, such as:

- A missing person

- Dementia (physically present, psychologically absent)

- Estrangement

- Incarceration

The uncertainty can make healing especially difficult.

6. Collective Grief

Communities or societies may grieve together after large-scale events such as pandemics, natural disasters, or mass tragedies. Collective grief can foster solidarity but may also overwhelm support systems (Eisma et al., 2020).

7. Cumulative (Secondary) Grief

This occurs when multiple losses accumulate over time — for example, losing several loved ones in a short period or experiencing job loss followed by a decline in health. The emotional load can become overwhelming (Rando, 1993).

8. Traumatic or Sudden Grief

Grief following unexpected or violent loss often overlaps with trauma responses. Individuals may experience intrusive memories, hypervigilance, or avoidance — symptoms similar to PTSD (Kristensen, Weisæth, & Heir, 2012).

These types often overlap—your grief may shift between them. Recognising yours reduces self-doubt and helps you seek appropriate support.

Common Misconceptions About Grief

Misconceptions create unnecessary pressure, shame, or isolation. Here are some of the most persistent myths,

1. Myth: Grief follows predictable, linear stages (denial → anger → bargaining → depression → acceptance).

Fact: Grief is non-linear, cyclical, and highly individual—no one goes through all stages, in order, or at all. Believing in strict stages can make people feel “stuck” or “doing it wrong.”

2. Myth: Grief and mourning are the same thing.

Fact: Grief is the internal emotional/cognitive experience; mourning is the external, cultural expression (e.g., ceremonial activities). Both are important; active mourning in safe spaces often aids healing.

3. Myth: You should “get over it,” “be strong,” move on quickly, or that “time heals all wounds” automatically.

Fact: Grief becomes part of life permanently; the goal is reconciliation, not erasure. Time alone doesn’t heal; active processing, support, and meaning-making do. Suppressing emotions prolongs pain; expression (tears, talking) is healthy.

4.Myth: Grief only follows death, and everyone grieves the same way or on a set timeline.

Fact: Any significant loss triggers grief (relationships, health, dreams, identity). Responses vary by personality, culture, support, and loss type—no universal intensity or schedule exists.

5.Myth: If you don’t cry outwardly, feel certain emotions, or show “intense” grief, you’re not grieving properly (or you’re weak/strong in the wrong way).

Fact: Grief manifests diversely—numbness, anger, relief, physical symptoms, or delayed reactions are all valid. Outward tears aren’t required; stoicism doesn’t mean absence of pain.

6.Myth: Strong people don’t grieve (or grief means weakness).

Fact: Vulnerability in grief is a form of courage. Repressing it leads to complications; honouring it builds resilience.

Why This Matters & Your Next Steps

Understanding these definitions, types, and myths reduces isolation, self-judgment, and confusion. It empowers you to name your experience, seek the right support (friends, therapy, communities like Hearty Talk), and recognise when professional help is needed (e.g., for prolonged grief).

Explore Further on Hearty Talk:

- Valentine’s Day Grief Guide for widows/widowers2026

- Valentine’s Day Survival Guide after Breakups and Divorce

Download our Grief Glossary & Gentle Reflection Prompts PDF—includes quick-reference definitions, types checklist, myth-busting summary, and journaling questions to help you process.

You’re Invited

Which definition, type, or misconception resonates most with you right now? Share anonymously in the comments or our Healing Stories section—your words can gently guide another heart.

Warmly,

Dr. Ezi & The Hearty Talk Team

Knowledge that reveals to heal.

Reference List

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed..).

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA dictionary of psychology.

Bonanno, G. A. (2009). The other side of sadness: What the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss. Basic Books.

Boss, P. (2006). Loss, trauma, and resilience: Therapeutic work with ambiguous loss. W. W. Norton.

Doka, K. J. (2002). Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Research Press.

Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031

Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. (1996). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis.

Kristensen, P., Weisæth, L., & Heir, T. (2012). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 75(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76

Neimeyer, R. A. (2019). Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Studies, 43(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1456620

Rando, T. A. (1993). Treatment of complicated mourning. Research Press.

Rosenblatt, P. C. (2017). Grief in small doses: Stories of loss and life. Routledge.

Shear, M. K. (2015). Complicated grief. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1315618

Shore, J., Gelber, M., Koch, R., & Sacks, N. (2016). Anticipatory grief: A review. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 12(1–2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000208

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Boerner, K. (2017). Cautioning health-care professionals: Bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 74(4), 455–473.